With this post,

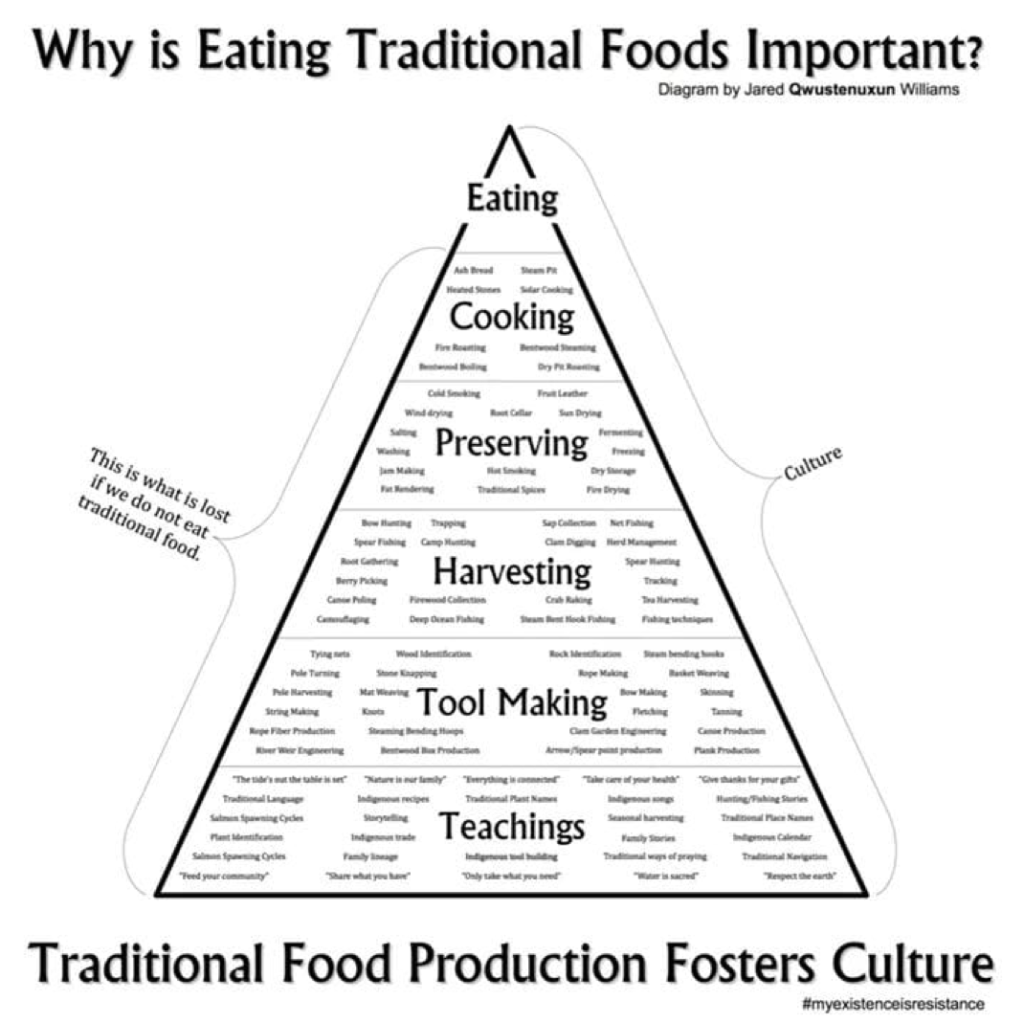

we invite you to reflect on how the very act of harvesting, hunting, and fishing is a powerful assertion of food sovereignty. Rather than seeing food sovereignty as a destination, we see it as a pathway made up of everyday acts of resistance and reparation accessible to everyone.

In the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, getting out in a canoe to harvest manoomin, or wild rice (Zizania palustris), is a political assertion of indigenous food sovereignty for Anishinaabe people. The act of getting together to harvest, and roast, or ‘parch’ manoomin by hand over a fire, is a revolutionary act in times of industrial, easy, and cheap food that disconnects us from our environment and from our community.